By Andy Bull (Guardian)

This is how it ends then, with Usain Bolt face down on the track, 10 metres out from the finish line. Just when you wondered whether Bolt was going to accelerate counter-clockwise around the earth to reverse time, or announce that he had to return to his home planet and then fly off into the night sky, or disappear with the princess into the happily-ever-after, all the dragons dead behind him, he gave us a last reminder that he’s only human after all. His hamstring went before he’d made it halfway home. He slowed to a halt while the field sped past him, then stumbled into a roll. It meant he crossed the line alone, and last. His first world championship final, in the 200m in 2005, finished the very same way.

After the race, Bolt’s three Jamaican team-mates all spoke about how long they had been made to wait in the call room before the race. Yohan Blake, Bolt’s friend and training partner, was furious, Omar McLeod distraught. “Ridiculous” was the word he used. After all the buildup, the International Assocation of Athletics Federations somehow managed to bungle Bolt’s farewell to the sport. The relay runners were made to wait 45 minutes backstage, while everyone in the stadium sat through the medal ceremonies and anthems for the men’s 5,000m and the women’s high jump. At this point, you wouldn’t trust the IAAF’s officials to fire a start gun without shooting themselves in the foot.

Part of the reason Bolt was made to wait so long was because Mo Farah was busy making his own farewell. The organisers had made a video montage of Farah’s greatest moments, intercut with a series of tributes from little kids, which they played on the big screens after the 5,000m was over. Farah, utterly spent after his desperate sprint to the line, seemed too busy sucking in fresh air to be moved by it. And for everyone else the effect was spoiled by the fact that Muktar Edris, who had dipped his hands to his head in imitation of Farah’s usual celebrations when he won the race, was dancing a merry jig up by the finish line at the time.

Still, Farah will be back, it’s just that next season he won’t be on the track because he’ll be on the road instead. But’s he’s running again in Birmingham on 20 August. Bolt had said he might run another race or two this season as well. But he’ll have to scrap that now. He’s gone for good. The IAAF has seen to that. Or at least, he will be come Monday. The IAAF has arranged a “special presentation” for him here on Sunday night, when he’ll get one last victory lap of the track, and, presumably, some profound apologies too. No doubt they’ll have a montage ready. But it won’t be a patch on the one that started playing in the memory the minute Bolt stepped out on to the track.

That first Saturday night in the Bird’s Nest in Beijing, when he spread his arms and seemed almost to stop to look around while he was 20 metres from the line, the giddy exhilaration that followed the first look at the clock stopped on 9.69sec. Then the 200m final days later, when Bolt dipped for the line, even though there was no one near him. He wasn’t competing against the field, but Michael Johnson’s untouchable world record. He turned 22 the next day, but was mischievous as a kid, and cheerfully admitted he’d eaten chicken nuggets for breakfast, lunch and dinner 10 days in a row.

Then August in Berlin a year later, when Bolt broke both his own records, so fast now that he stretched the outer limits of possibility, as if we had to draw new maps to reflect our understanding of how far, and how fast, human beings can go. Or Daegu in 2011, when we finally saw him flustered. He was disqualified for a false start. It was the only way anyone was going to beat him. At the London Olympics a year later, he had a real rival, Yohan Blake. At least, that’s what we told ourselves before the Games.

A fortnight later, when Bolt crossed the line first in the 200m, he held his finger to his lips, admonishing everyone who doubted him. Then he dropped to the track and started doing push-ups while Dizzee Rascal’s Bonkers blasted out over the stadium PA. It was the iconic image of his Games. Well, that and the selfie he posted with the Swedish women’s handball team at 3am in his hotel room the night after he won the 100m. “I’m now a legend,” he said that night, “I’m also the greatest athlete to live.” Who was going to argue? Justin Gatlin tried. He spent the next three years coming for Bolt, in Moscow and then again in Beijing. But he didn’t catch him.

In 2016, there was the triple-triple, his third set of three Olympic gold medals and that photo of him cocking his head to shoot a grin at the camera as he finished his 100m semi-final, the roadrunner taunting seven coyotes. And then last Saturday, when Gatlin finally beat him in a big race. And even that, in its bittersweet way, burnished his legend. Bolt could have quit in 2016. He had no reason to be at these world championships. He had nothing left to prove, and nothing left to win, but he came anyway, to put it all on the line one last time. He was willing to gamble, and he lost, twice. There’s something to admire in that, too. Truth is, the IAAF doesn’t deserve him, and never did.

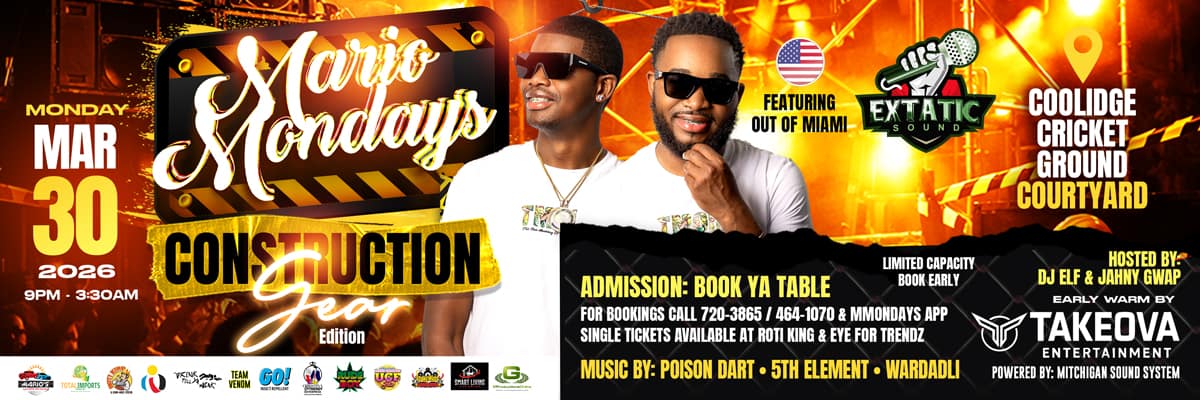

Advertise with the mоѕt vіѕіtеd nеwѕ ѕіtе іn Antigua!

We offer fully customizable and flexible digital marketing packages.

Contact us at [email protected]