By Anthony Faiola

For the Chagossians, the island of Diego Garcia became a paradise lost. In the late 1960s, Britain began forcibly removing the inhabitants of the Indian Ocean atoll — most of them the descendants of enslaved people and laborers — to make way for a U.S. military base. Suing for restitution to this day, the expelled Chagossians would suffer lives as second-class citizens far from their impossibly turquoise shores.

After the middling results of COP26 — the U.N. climate summit in Glasgow, Scotland — the world may be doing to the residents of small island states what British soldiers did to the Chagossians: sentencing them to forced exile. The half-promises and open timelines for turning the clock back on emissions and weaning the world’s energy grids off fossil fuels, island leaders say, is effectively dooming their societies to go the way of Atlantis.

The cluster of island nations — many of them low lying, with rising tides already licking further into shore — may be the biggest losers of the Glasgow summit. So grim was the outlook ahead of a final agreement that the South Pacific state of Tuvalu — whose foreign minister delivered a summit speech by video, knee deep in the ocean while wearing a suit — announced it was already looking for ways to at least claim maritime rights over the segment of ocean that will ultimately drown its tiny nation of 12,000 people.

The mood darkened further after the final wording of the Glasgow Climate Pact on Sunday saw India and China successfully water down a pledge to “phase out” fossil fuels, replacing that wording with the more ambiguous “phase down.”

“Phasing ‘down’ coal? Really?” Gaston Browne, prime minister of Antigua and Barbuda, an island country lying between the Caribbean Sea and the Atlantic Ocean, told me by phone this week. “This should have been about phasing out. The very language they are using shows us that they are trying to game the system. For us in the Caribbean, in the Pacific Ocean, this is imperiling our very existence.”

At the Paris climate summit in 2015, large emitters succeeded in shifting the legal conversation away from “compensation” for climate-related loss and damage in heavily impacted states, and toward the notion of voluntary aid. But they have dragged their heels on providing even that — with nations only vaguely agreeing last week to start a “dialogue” on the question.

Now, a group of frustrated island states have come to the conclusion that the time has come to play less nice. In Scotland, Antigua and Barbuda signed a new agreement with Tuvalu, recently joined by Palau, aimed at finding legal levers to compel large emitters to pay a price for the destruction in island states.

Their legal avenues are challenging, but not closed. They could seek an opinion at the International Court of Justice (ICJ) on whether nations can be held legally responsible for the impact of their emissions on other countries. But referral to the court requires the support of a United Nations body such as the General Assembly — a hurdle island states tried and failed to scale in 2012, in part due to fears that a court decision could muddy the waters at future climate talks. Vanuatu, another vulnerable island nation, is making a new bid for an ICJ opinion now. Another option could be sidestepping the assembly and seeking an opinion from the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea in Hamburg, established by a U.N. convention in 1982.

Though not legally binding, an advisory opinion from either tribunal could be used as leverage both in climate negotiations and further legal challenges in domestic or international courts.

Payam Akhavan, legal counsel for the newly formed Commission of Small Island States on Climate Change and International Law, summed up the objective this way: “You pollute, you pay.”

“There may have been a time in the 1980s when we didn’t know what the consequences were of global warming,” he said. “But now, we do. And it’s inflicting irreparable harm on island states.”

Almost without exception, the United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction has said, small island states are at great risk from projected impacts of climate change. The problems they face vary. But the biggest questions in any legal fight are likely to be these: How do you put a price tag on a lost society? Does it just include the cost of relocating inhabitants? Or should the damages be far more?

This much we do know: Sea level rise within the next century could submerge entire Pacific nations, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change warned this year. As my colleagues reported, Tuvalu, midway between Hawaii and Australia, has an average land elevation of 6 feet 6 inches above mean sea level, with the water rising at almost 0.2 inches each year. Do the math, and those apocalyptic predictions seem conservative.

Already, waters that once were “gin-clear are now cloudy with sand,” my colleagues noted. Taro and cassava — long locally grown — are now imported. Rising seas have contaminated fresh groundwater supplies, making Tuvalu directly reliant on rainwater. Talk is growing of the relocation of its residents to New Zealand, Australia or Fiji.

“The reality is that in the future, the Tuvaluan community is likely to be fragmented among many different countries,” Jordan Emont and Gowri Anandarajah wrote in the American Medical Association Journal of Ethics.

Island states additionally face outsize impacts from rising salination, droughts, heavy rains and coral bleaching. In the Caribbean, more extreme weather during hurricane season is a particular threat.

Few nations understand that risk more than Browne’s. In 2017, I ventured to Barbuda, the smaller of Antigua and Barbuda’s main islands, to document Hurricane Irma’s devastating impact there. Virtually no structure went undamaged in that singular, society-crushing disaster. Its 1,800 people evacuated from the island, Barbuda had gone feral within a week. Abandoned dogs formed packs and were taking down livestock. At the damaged hospital, the medical dorms were a scrap heap. An ambulance was wedged into a tree.

The devastation triggered bitter disputes between Barbudans and the central government in Antigua over how to rebuild. Of the international pledges for help that Browne said initially numbered in the “billions of dollars,” only about $22 million actually materialized. More than four years later, Browne said, only 70 percent of the island is rebuilt.

Asked why he was so disappointed in the summit in Scotland, he replied: “Because for us, climate change is not a theoretical construct. We are seeing more frequent and more ferocious hurricanes, we are having heat waves, brush fires. We’ve lost some of our most beautiful beaches. We’re losing our coral reefs from warming temperatures. Last year, we had one of the worst floods in our history. For us, this is a life and death.”

Unlike the Chagossians, most Barbudans returned home.

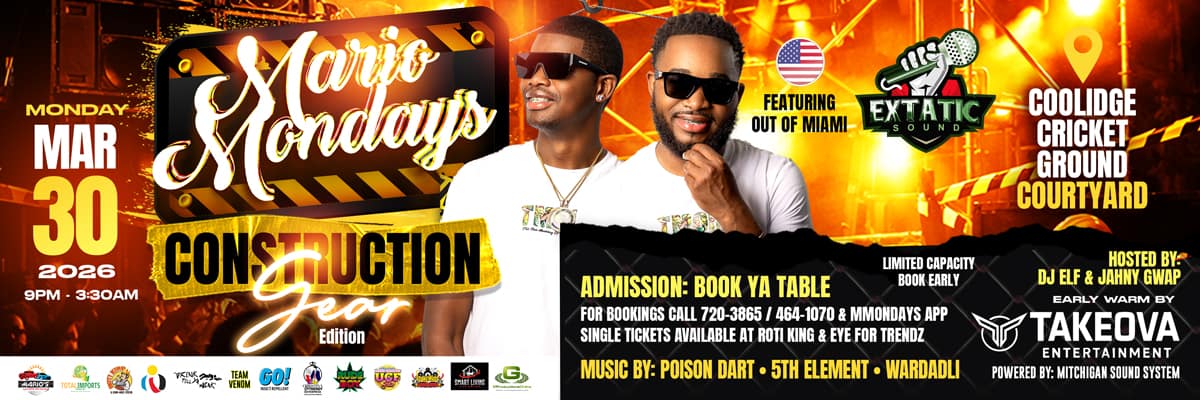

Advertise with the mоѕt vіѕіtеd nеwѕ ѕіtе іn Antigua!

We offer fully customizable and flexible digital marketing packages.

Contact us at [email protected]