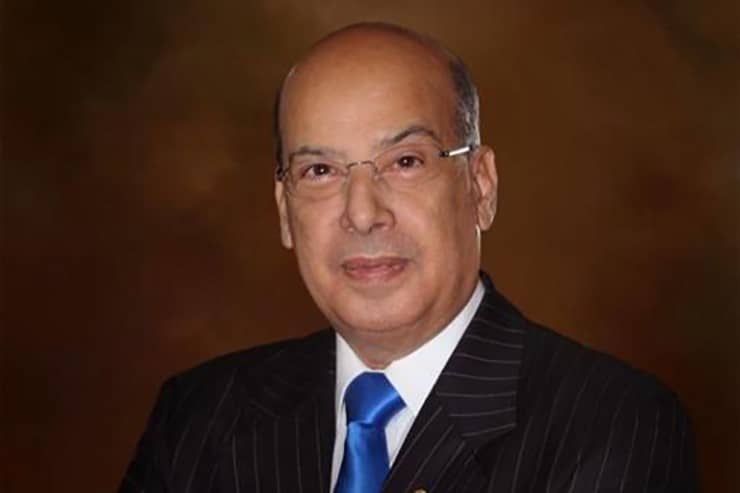

By Sir Ronald Sanders

On January 14, 2026, the U.S. Department of State announced that, effective January 21, it would pause the issuance of all immigrant visas for nationals of 75 countries, including eleven in the Caribbean Community (CARICOM), deemed to be at “high risk of public benefits usage.” Applications may still be submitted, but no immigrant visas will be issued during the pause.

The notice sets out the policy logic plainly. President Donald Trump has directed that immigrants must be financially self-sufficient and must not become a “public charge.” Visas are described as a privilege, not a right, and admissions as national-security decisions. Implemented by a Department led by Secretary Marco Rubio, the language is deliberate and categorical. It signals a shift in doctrine, not a temporary pause awaiting reversal.

For the Caribbean, this matters because for decades outward migration absorbed part of the region’s internal economic pressure—unemployment, low wages, limited domestic markets, and frustrated professionals. That outlet has now narrowed. The pressure, therefore, will intensify at home.

The composition of the 75-country list reveals the underlying logic. The countries are drawn overwhelmingly from the Global South—Africa, Latin America and the Caribbean, the Middle East, and parts of Central and Eastern Europe and Asia. What links them is not politics or proximity, but economic structure: high youth populations, weak labour absorption, persistent underemployment, and long reliance on outward migration to relieve domestic pressure. The pause thus functions as a broad structural screen, signalling that the United States will no longer accept migrants it does not actively seek.

It is now incumbent on the eleven CARICOM states to build conditions that attract investment, expand enterprise, and generate employment. The alternative is clear and costly: higher unemployment, deepening poverty, rising crime, social instability, and declining economic prospects.

This warning is not speculative. Research by the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank, and the Inter-American Development Bank shows a consistent pattern across Latin America and the Caribbean: persistent unemployment—especially among youth—drives poverty, fuels crime, weakens social cohesion, and deters investment. Stronger labour markets and rising real earnings, by contrast, are among the most reliable drivers of poverty reduction and stability.

Addressing these challenges, however, is not the responsibility of governments alone. It requires a collective national effort.

Governments must create conditions for growth—but they do not create jobs on their own. The private sector must invest, expand, innovate, and take calculated risks at home, not merely extract rents or wait for incentives. Trade unions must defend workers, while engaging seriously with productivity, skills upgrading, and enterprise sustainability. Political parties—especially those that aspire to govern—must treat economic reform as a national obligation, not a partisan weapon.

If this collective effort fails—if no national plan is jointly devised, implemented, and monitored—Caribbean economies will fracture under the weight of unemployment, accompanied by familiar cycles of bickering and finger-pointing among actors unwilling to place national interest above sectional advantage.

The region’s difficulties are compounded by a self-inflicted handicap. World Bank and IDB assessments show that many Caribbean economies operate with high costs of doing business—slow approvals, overlapping regulation, expensive logistics, and especially high energy prices. Electricity costs in some states are two to three times higher than in North America. Regulation is often cumbersome, mired in red tape and institutional inertia, and in some cases distorted by practices that extract private gain for favourable treatment.

Too often, reform is postponed because it is inconvenient. Governments fear backlash. Businesses resist competition. Unions resist change. Oppositions calculate advantage. The political cost of reform is exaggerated; the economic cost of delay is discounted.

That miscalculation is no longer theoretical. It is urgent. If unemployment remains high while migration outlets narrow, the result will not be patience. It will be rising poverty, higher crime, social strain, and a deteriorating investment climate. Investors will withdraw. Insurance costs will rise. Bank deposits will shrink and interest rates increase. Tourism will falter. Public finances will weaken. Social cohesion will fray.

This is why responsibility must now be shared—and openly acknowledged as such. CARICOM must also take its own commitments seriously. The Revised Treaty of Chaguaramas envisaged a regional industrial policy under the CSME. Heads of Government are expected to consider a CARICOM Industrial Policy Framework at their Fiftieth Meeting in St. Kitts and Nevis next month—more than three decades after the Treaty was signed.

Similarly, the Caribbean Skills Certificate and regional labour mobility were intended to create a genuine internal market for skills. They have yet to deliver at scale. Initiatives to deepen capital and financial-market integration—such as the long-promised regional stock exchange championed by the CARICOM Private Sector Organization—remain worthy causes deserving urgent support.

If external doors are narrowing, the region must make its internal space work—or accept the cost of fragmentation. What is required now is a new compact. Governments must lower the cost of doing business decisively. The private sector must commit capital and creativity to domestic production. Trade unions must champion skills, productivity, and fair wages together. Political parties must accept that economic reform is not optional, and that sabotaging it for short-term gain undermines everyone’s future.

The State Department’s notice does not single out the Caribbean, but its consequences should rivet regional attention. It removes the long-standing illusion that migration will always be available as a safety valve. That era is all but over. The door to migration to the United States is no longer ajar; it has been closed elsewhere for years.

Either Caribbean societies—governments, businesses, unions, and political movements alike—accept shared responsibility for building opportunity at home, or they continue to defer and allow unemployment, crime, and instability to exact a far higher price.

As migration closes, there is only one viable response: build opportunities for investment and jobs at home—together.

(The author is the Ambassador of Antigua and Barbuda to the United States and the OAS, and Dean of the OAS Ambassadors accredited to the OAS. Responses and previous commentaries: www.sirronaldsanders.com)

Advertise with the mоѕt vіѕіtеd nеwѕ ѕіtе іn Antigua!

We offer fully customizable and flexible digital marketing packages.

Contact us at [email protected]

Ain’t nobody trying to read all this nonsense.

Oh, only now this is realised? Also it’s funny that this was said after Gaston claim Antigua is so good emigration is not needed. Inequality causes crime especially when youth unemployment is high, only thing Caribbean countries care about is tourism and have let everything else died, when counties only build infrastructure to cater to tourism and not anything else it pisses people off. The jobs that we already have have have not seen wages increase when Antigua is said to be thriving so only upper class sees benefits while everything else crushes the middle and make the working class poorer from the tax system which tax working class more than the upper and now benefitting from housing plans to give them multiple homes to rent out and air BnB.

Highest paid ambassador in the world, the logistical expense that the tax payers will have to be burdened with to extract him from Guyana on charter flights or long distance telephone bills to go to the USA validate Gaston group who needs white supervision is a costly millstone around antigua and Barbuda tax payers neck.

Comments are closed.