Amid CARICOM-Trinidad and Tobago Tension, Leaders Meet

By Dr. Nand C. Bardouille

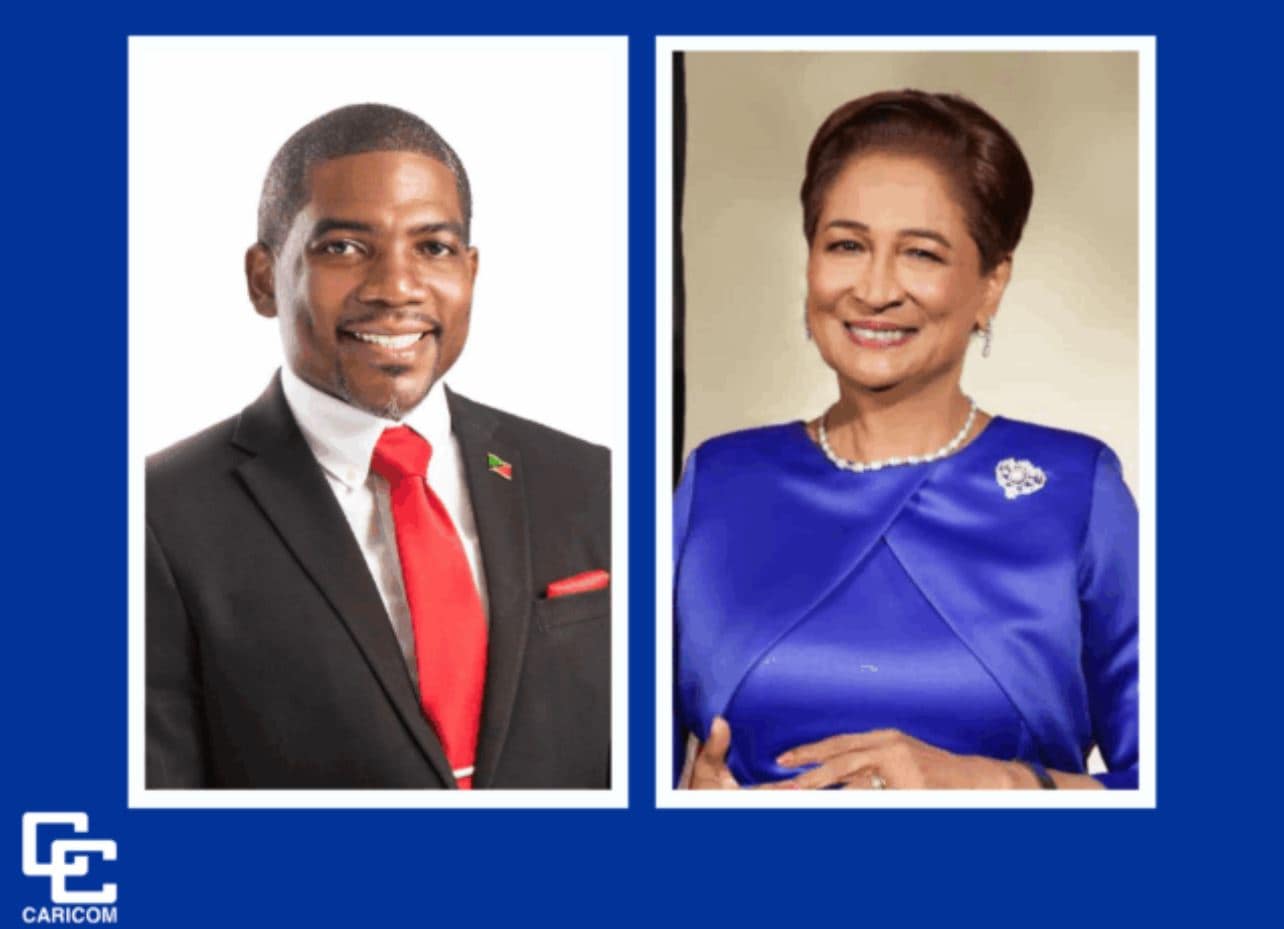

On January 30, along with a team that included Caribbean Community (CARICOM) Secretary General Carla Barnett, Prime Minister of St. Kitts and Nevis Terrance Drew paid an official visit to Trinidad and Tobago. Drew met with the Prime Minister of Trinidad and Tobago, Kamla Persad-Bissessar, in his capacity as the current Chair of CARICOM.

An official statement, issued by Drew’s Office ahead of this visit, indicated (in part): “During the visit, Dr. Drew is expected to meet with the Prime Minister of Trinidad and Tobago, Hon. Kamla Persad-Bissessar, along with members of her Cabinet and senior officials, to discuss matters of regional importance.”

While a specific set of outcomes of this meeting is not yet clear, signs of progress emerged after these two leaders’ high-profile engagement.

Persad-Bissessar called her discussions with Drew “productive,” expressing her government’s support for CARICOM. Her softened — though restrained — stance on CARICOM contrasts with previous criticism of the bloc.

For his part, Drew viewed the meeting as “very constructive.” This is in a context where that particular engagement is regarded as perhaps the most consequential one in respect of “the Chair’s focus on face-to-face discussions with regional leaders.”

This ongoing engagement has its origins in Drew’s clarion call for “managing our dialogue with care, mutual respect, and a resolute sense of regional responsibility.”

He made this appeal at a critical juncture in international politics. The ubiquity of America’s foreign policy cudgel has fundamentally altered the politics of regionalism in CARICOM, which has also fallen into the clutches of the current U.S. administration’s “Donroe Doctrine.”

Each of the bloc’s 14 sovereign member states has considerable bilateral interests with the United States. Traditionally, cognizant of those respective interests’ wider implications for CARICOM, these countries’ governments have worked closely with each other on U.S.-related foreign policy matters.

The meeting between Drew and Persad-Bissessar aimed to address some of the latest developments regarding regional issues, amid strained relations between Trinidad and Tobago and most other CARICOM member states.

Trinidad and Tobago’s support of U.S. military deployments that ultimately led to the ouster of now former Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro and ushered in a post-Maduro “transition” in Venezuela has been at the centre of a foreign policy-related split among CARICOM member states, undermining regional unity and a historically cooperative foreign policy approach.

Port of Spain has taken a harder line against those CARICOM member states that — with an eye to ‘Operation Southern Spear’ and ‘Operation Absolute Resolve’ — express reservations about the use of this form of power and the narrative qua pretext to leverage it.

This state of affairs is a serious concern for CARICOM, especially as common ground has been elusive thus far.

CARICOM insiders have tied the way forward to Drew’s bilateral outreach to his colleague Heads of Government with due regard to an all-important CARICOM summit this month. The Fiftieth Regular Meeting of the Conference of CARICOM Heads of Government, carded for February 24 to 27 in St. Kitts and Nevis, takes place under Drew’s chairmanship.

This summit comes against the backdrop of the bloc having arrived at an inflection point. CARICOM member states’ long-held unified stance against hard power in international relations is reshaping before our very eyes. Importantly, CARICOM faces a split on whether to seek accommodation with U.S. foreign policy for security.

What now obtains are competing visions of how to grapple with the stark reality of international relations that, increasingly, is driven by predation.

One camp within the regional grouping links the majority of member states, whose foreign policy outlook is still defined by shared opposition to the notion of a hierarchical international order of dominant and subordinate states.

The other camp downplays the wider effects qua implications of international politics’ hard power dimension, which hinges on a United Nations Charter-suppressing might is right foreign policy ethos.

In such a foreign policy power play, a given country wilfully sidesteps international norms and laws. In this situation, having rationalized hierarchical relationships, it pursues its desired foreign policy outcomes by bringing military force and/or economic might to bear on compelling compliance from other (state) actors in the international system.

Having regard to Trinidad and Tobago’s sharp shift in its foreign policy towards support for U.S. interventionism, it fits squarely into this second camp. This development marks one of the most consequential reversals in the conduct of Trinidad and Tobago’s post-independence international relations, undercutting CARICOM’s recourse to multilateral power. (This kind of power leans into the processes of international cooperation and multilateralism that stand as a bulwark against hard power, amplifying the voice of small states on the international stage.)

In combination, these foreign policy-related developments end up backstopping the exercise of hard power in international relations.

And yet hard power is challenging CARICOM member states, testing their sovereignty and internal coherence. I have read this to mean that external pressure is impactful mainly when regional actors disagree on responses, revealing vulnerabilities in unity.

Any attempt to normalize an approach to international relations that is skewed to hard power undermines small states’ long-term interests, considering their reliance on the rules-based international order — rather than force — for their survival. Moreover, it signals a willingness to constrain and diminish CARICOM’s multilateralism-related room for manoeuvre.

Now CARICOM needs to demonstrate it can muster a collective response to a geopolitical trend line that threatens its member states’ post-independence gains on the international stage.

On the occasion of its upcoming summit, then, the regional grouping would do well to issue a call to action on foreign policy that might allow it to deal with the hard power turn in international politics as best it can.

________

Nand C. Bardouille, Ph.D., is the manager of The Diplomatic Academy of the Caribbean in the Institute of International Relations at The University of the West Indies (The UWI) St. Augustine Campus, Republic of Trinidad and Tobago. The views expressed here are his own.

My article for the Jamaica Gleaner titled ‘CARICOM’s Inflection Point’ — published on February 2, 2026 and available online — takes a deep dive into the subject matter of the foregoing analysis.

The Honourable Dr. Terrance Drew, Prime Minister of St. Kitts and Nevis and the current Chair of the Caribbean Community (left)

The Honourable Kamla Persad-Bissessar, SC, Prime Minister of Trinidad and Tobago (right)

Photos courtesy of the CARICOM Secretariat.

Dr. Nand C. Bardouille

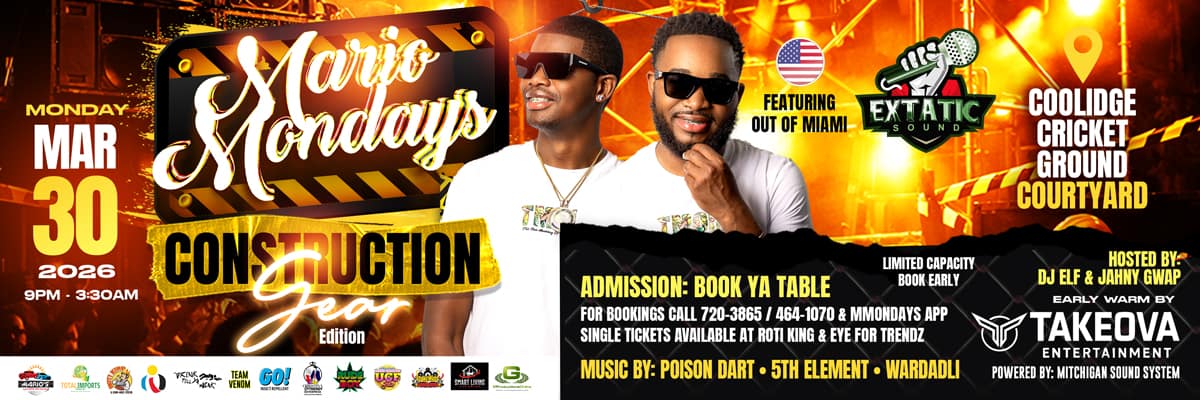

Advertise with the mоѕt vіѕіtеd nеwѕ ѕіtе іn Antigua!

We offer fully customizable and flexible digital marketing packages.

Contact us at [email protected]