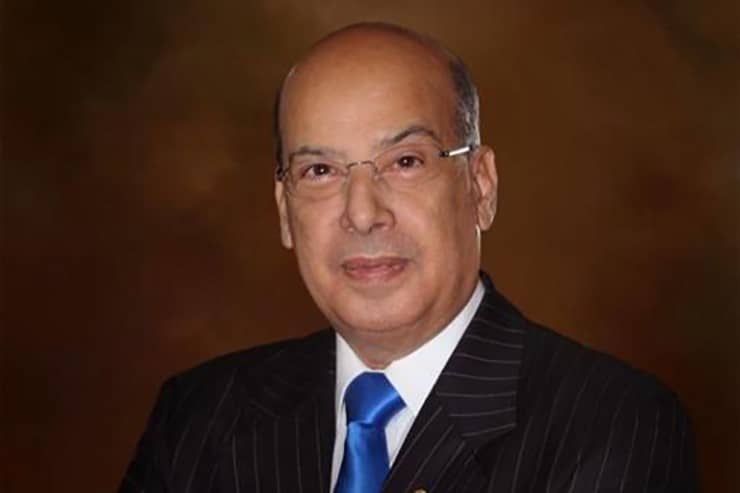

By Sir Ronald Sanders

As 2025 draws to a close, the Caribbean Community stands at a moment that calls for less rhetoric and more realism. CARICOM is experiencing a period in which external pressure is intensifying, new norms are hardening among powerful states, and the need for small states to navigate emerging demands is growing.

The central challenge before CARICOM is not disagreement between governments. Diversity of view is inevitable among governments, which are transient by nature and whose policies are shaped by domestic political cycles. The deeper question is whether all governments—acting as a community of interests—can strengthen collective planning and coordination in a world where economic, political and security shocks increasingly spill across borders.

Economic stress in one CARICOM country never remains confined. The region’s economies are interlinked through trade, investment, labour movement, tourism and financial flows. Intra-CARICOM exports—particularly from the more industrialised CARICOM economies—have direct implications for revenues, employment and growth across the Community. A downturn in any one economy translates into lost income and reduced demand across regional supply chains.

Political stress behaves similarly. When a member state faces external pressure or coercion, even well-intended but qualified support within the Community can dilute deterrence, signal hesitation and encourage further testing of regional resolve. Therefore, CARICOM’s unity must be expressed not only in declarations, but in timely, consistent and unambiguous collective action.

This reality applies equally to Guyana. Oil and gas revenues have transformed its national prospects, but wealth does not confer immunity from geopolitical risk or diplomatic pressure. Guyana looks to all CARICOM governments for political and diplomatic support on matters touching its territorial integrity—just as Belize has long relied on the Community’s consistent backing in defence of its borders and independence. A weakened Community would be less persuasive in defending its members when pressure mounts. That is why Guyana and Belize, no less than others, have a stake in helping to bolster the economic resilience of all CARICOM countries.

Against this backdrop, recent public questioning of CARICOM’s reliability misses the larger point. For more than 50 years, CARICOM has provided a framework for cooperation in trade, security, health, disaster response and diplomacy. The record is imperfect, but the outcomes are real—and without them, individual states would be far more exposed.

In security, the facts are clear. CARICOM does not support drug trafficking, organised crime or illicit enterprise. On the contrary, the Community has worked closely with each other and with international partners, including the United States, through intelligence-sharing, law-enforcement coordination and maritime security mechanisms. These arrangements are professional, active and indispensable.

Similarly, CARICOM’s advocacy of the Caribbean as a zone of peace reflects respect for international law, the peaceful settlement of disputes and the recognition that stability is the foundation of economic survival. For small states, peace is a necessary condition for prosperity.

What distinguishes this moment is the accumulation of pressures that now require greater collaboration, not less.

Storm clouds are forming over the citizenship-by-investment (CBI) programmes operated by five CARICOM states. The European Union has signalled a decisive hardening of its position, suggesting that the existence of such programmes may, in itself, justify the suspension of visa-free travel to the Schengen area, regardless of reforms undertaken—a shift from conditional scrutiny to structural opposition.

At the same time, the United States has made clear that CBI programmes across the region are under close scrutiny, with particular focus on identity verification, security vetting and the integrity of passport issuance. If these pressures intensify, the consequences will extend beyond the five states involved, affecting investment flows, fiscal stability, financial services and confidence across the region.

This is why the countries that operate CBI programmes must redouble their efforts to ensure that applicant vetting meets the highest international standards; that jointly agreed regulatory and oversight frameworks are fully and consistently implemented; that breaches attract prompt sanctions; and that the systems are insulated from corruption or political interference. Every reasonable step must be taken to reassure international partners that Caribbean CBI programmes are secure, credible and effectively enforced.

Visa policy has also become a sharper instrument of leverage in international relations. Measures applied to one country can widen unless concerns are addressed early and collectively. The economies of all CARICOM states depend on mobility for tourism, education, business travel, remittances and diaspora engagement. No government can afford a fragmented response.

Another pressure point has emerged around the Cuban medical cooperation programme, which in 2025 became a central issue in US policy towards Latin America and the Caribbean. Governments face a genuine dilemma: health systems rely heavily on these medical personnel, yet geopolitical realities and international conventions cannot be ignored. Responsible governance requires preparation—developing alternatives to protect public health services—while engaging candidly with all partners, including Cuba.

These challenges share a common feature. Each reflects the asymmetry of power between small states and larger partners. None can be managed effectively by individual countries acting alone. All underscore the need for reciprocity in international relations.

Cooperation, however, cannot mean acquiescence without regard to consequence. If small states are expected to alter policies that affect livelihoods, revenues and social stability, then powerful partners must recognise the costs imposed and engage in solutions that preserve viability, not merely compliance. Reciprocity must be negotiated and agreed—not imposed.

For the Caribbean, strong and predictable relations with the United States remain indispensable. The region’s objective must be partnership that recognises the constraints small states face and the shared benefits of stability, growth and democratic resilience.

CARICOM’s task is clear. The Community must move from coordination after the fact to planning in advance: shared risk assessment, early consultation and collective strategies that prevent external pressures from forcing unilateral decisions.

As 2026 begins, CARICOM faces a choice. It can treat each challenge as a national problem to be managed alone or recognise that the future resilience of the Caribbean depends on planning together, speaking with discipline and acting with foresight.

In a world where power is impatient and rules are applied unevenly, small states endure not by standing apart, but by standing together—clear-eyed about risks, prepared for change and united in purpose. That should be the work of every CARICOM government in the year ahead.

(The author is the Ambassador of Antigua and Barbuda to the United States and the OAS, and Dean of the OAS Ambassadors accredited to the OAS. Responses and previous commentaries: www.sirronaldsanders.com)

Advertise with the mоѕt vіѕіtеd nеwѕ ѕіtе іn Antigua!

We offer fully customizable and flexible digital marketing packages.

Contact us at [email protected]

TRINIDAD and TOBAGO is a SOVEREIGN NATION.

A MANDATE was given by the ELECTORATE to PRIME MINISTER KAMLA PERSAD-BISSESSAR to EXECUTE her duties as she sees fit in the interest of TRINIDAD and TOBAGO CITIZENS.

CARICOM is DYSFUNCTIONAL.It is all about RACISM, CRIMANALITY, OPPRESSION and NARCO DRUGS that kills over 100,000 BLACK,WHITE,BROWN sons and daughters every year in the UNITED STATES of AMERICA .CARICOM also supports VENEZUELA NARCO TERROIST DICTATOR MADURO and COMMUNIST CUBA REGIME that OPPRESSES ITS PEOPLE DENY FREEDOM OF SPEECH AND HUMAN RIGHTS.

You go take a leak and get off our tax payers back with that exorbitant salary and housing and transportation abroad that you enjoy through the ALP and Gaston who wants white supervision.

Comments are closed.