BBC: Insects are a nutrition-dense source of protein embraced by much of the world. Why are some of us so squeamish about eating them?

The idea of biting into a burger made from crushed crickets or mixing mealworms into your fried rice may take a little getting used to. But even if the thought of eating insects turns your stomach now, bugs could – and some researchers say should – form an important part of our diet.

While the West might be unusually squeamish about insects, people have been eating them for thousands of years, and in many parts of the world the practice is commonplace. Around 2,000 insect species are eaten worldwide in countries across Asia, South America and Africa. In Thailand, heaped trays of crisp deep-fried grasshoppers are sold at markets and in Japan wasp larvae – eaten live – are a delicacy.

et in Europe, just 10% of people would be willing to replace meat with insects, according to a survey by the European Consumer Organisation. To some, this unwillingness to eat insects is a missed opportunity.

“Insects are a really important missing piece of the food system,” says Virginia Emery, chief executive of Beta Hatch, a US start-up that creates livestock feed out of mealworms. “[They] are definitely a superfood. Super nutrient dense, just a whole lot of nutrition in a really small package.”

Because of this, farmed insects could help tackle two of the world’s biggest problems at once: food insecurity and the climate crisis. (Watch our video on how insects are the missing link in our food chain above or on BBC Reel)

Agriculture is the biggest driver of global biodiversity loss and a major contributor to greenhouse gas emissions. Rearing livestock accounts for 14.5% of global greenhouse gas emissions, according to the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO).

“We’re in the middle of a biodiversity mass extinction, we’re in the middle of a climate crisis, and yet we somehow need to feed a growing population at the same time,” says entomologist Sarah Beynon, who develops insect-based food at the Bug Farm in Pembrokeshire, Wales. “We have to make a change and we have to make a big change.”

Insect cultivation uses a fraction of the land, energy and water required for traditional farming, and has a significantly lower carbon footprint. Crickets produce up to 80% less methane than cows and 8-12 times less ammonia than pigs, according to a study by researchers at the University of Wageningen in the Netherlands. Methane is a highly potent greenhouse gas which, although shorter-lived in the atmosphere, has a global warming impact 84 times higher than CO2 over a 20-year period. Ammonia is a pungent gas and air pollutant that causes soil acidification, groundwater pollution and ecosystem damage.

Farming insects worldwide would free up vast tracts of land that are currently used to farm animals as well as produce feed for livestock. Replacing half of the meat eaten worldwide with mealworms and crickets has the potential to cut farmland use by a third, freeing up 1,680 million hectares of land, equivalent to around 70 times the area of the UK. This could slash global emissions, according to a study from the University of Edinburgh.

“Looking at a yield of protein per area, insect farming uses around an eighth of the land compared to beef,” says lead author Peter Alexander, a senior researcher in food security at the University of Edinburgh. Despite these findings, Alexander says eating a bean burger is the more sustainable option, as less energy is used to grow the plants than raise insects.

However, Tilly Collins, a senior teaching fellow at the Centre for Environmental Policy at Imperial College in London, argues that insects can fulfil some needs that plant-based foods can’t. “Plant-based diets often come with substantial carbon mileage. A lot of plants that people are wanting to eat have disastrous environmental consequences,” she says. “Efficiently farming insects is preferable.”

Collins says insects could provide an especially important source of nutrition in developing countries. “We have a very good diet in the UK. We rarely lack nutrition. But in Africa that is not the case,” she says, noting that many African countries are rapidly scaling up production of insects to feed both humans and animals.

In many ways, insect farming is an example of efficiency turned into a fine art. Firstly there is the speed at which insects grow, reaching maturity in days, rather than the months or years it takes livestock, and they can produce thousands of offspring.

Then there’s the fact that insects are 12 to 25 times more efficient at converting their food into protein than animals, says Beynon. Crickets need six times less feed than cattle, four times less than sheep and two times less than pigs, according to the FAO. One of the main reasons behind this efficiency is because insects are cold-blooded and therefore waste less energy maintaining their body heat, says Alexander, though some species need to be reared in a warm environment.

Insect farming also produces much less waste. “With animals a lot of the meat is wasted. With insects we would eat the whole thing,” says Alexander.

And as well as producing less waste, insects can also live off food and biomass that would otherwise be thrown away, says Collins, contributing to the circular economy, where resources are recycled and reused. Insects can be fed agricultural waste, such as the stems and stalks from plants that people don’t eat, or scraps of food waste. To complete the recycling chain, their excrement can be used as fertiliser for crops.

Despite the strong sustainability credentials and nutritional value associated with eating insects, there is a long way to go before they feature in any big way in Western diets.

“We associate insects with everything but food,” says Giovanni Sagari, a food consumer researcher. “I mean with dirt, danger, with something disgusting, with something that makes us feel sick.”

But attitudes are starting to change. By 2027, the edible insects market is projected to reach $4.63bn (£3.36bn) and European companies are investing in edible insects following approval from the European Food Safety Authority.

“People’s perceptions of food do change, but slowly,” says Alexander. He points to the example of lobster, which for many years was considered a highly undesirable food and often served in prisons, before it became a luxury good. “It was so plentiful that there was a law forbidding people from feeding lobster to prisoners more than twice a week.”

Sagari says the best commercial proposition is to grind insects into powders and include them in processed food, rather than serving them whole as a snack. Chef Andy Holcroft who runs the UK’s first edible insect restaurant at the Bug Farm agrees with this assessment.

“Rather than sprinkling whole insects on a salad… I thought if we’re going to get it accepted into mainstream food culture, the best way is to incorporate it as a percentage of the overall whole product,” says Holcroft.

“At the end of the day, you might have the healthiest, most nutritional, most sustainable product but unless it tastes nice and people are willing to accept it, it may be a lot more difficult to get that across.”

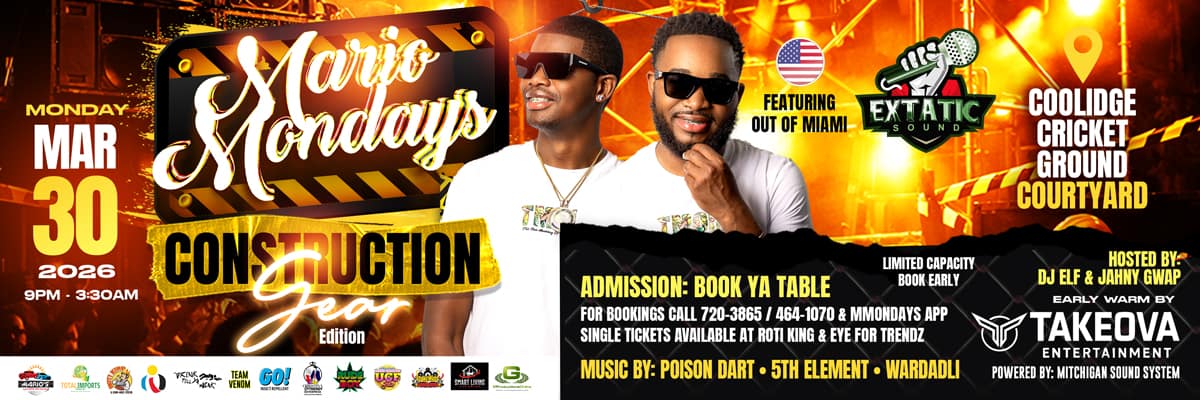

Advertise with the mоѕt vіѕіtеd nеwѕ ѕіtе іn Antigua!

We offer fully customizable and flexible digital marketing packages.

Contact us at [email protected]

Lard help us

We should pay our elected officials with this super food instead of money. After all, they ‘claim’ to support the World Economic Forum’s global sustainability initiative don’t they. They should LOVE this idea!

Chow time Gaston Brown…. 😃

In some Countries around the world. They do eat grubs and worms. They always insisted they are a source of protein. I always tell them. Not for this man ya. I am a fussy eater. If I did not eat it. While growing up in Antigua. I do not eat it now.

So, we’re going from “Waiter, there’s a roach in my food!!!” to….

“Waiter, there aren’t enough roaches in my food!!!”

Lol. Folks, it looks like Baygon will soon start selling chewables for those times when you food just won’t stay down…

Comments are closed.